STATUES IN SOCIAL CONTEXT

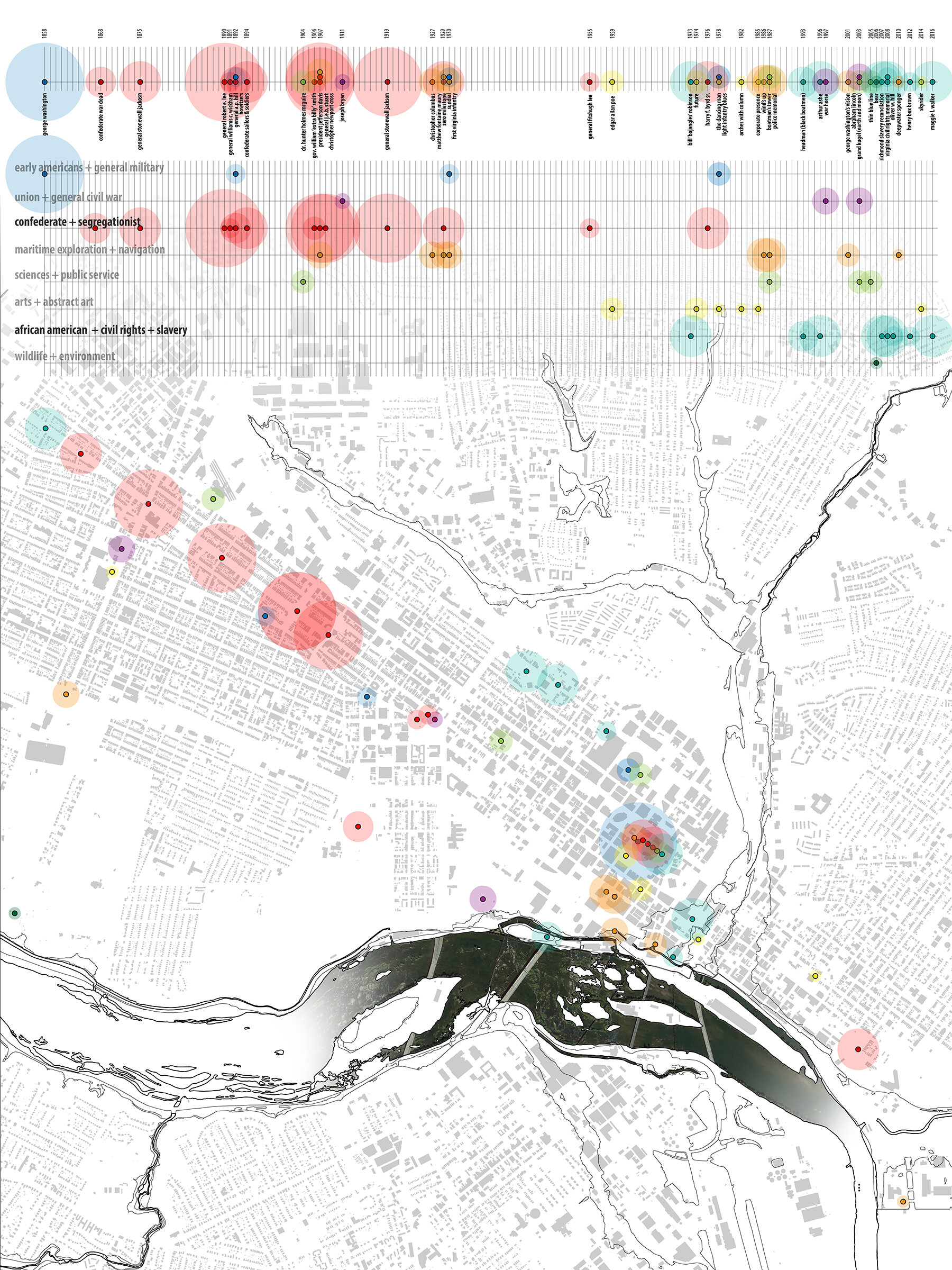

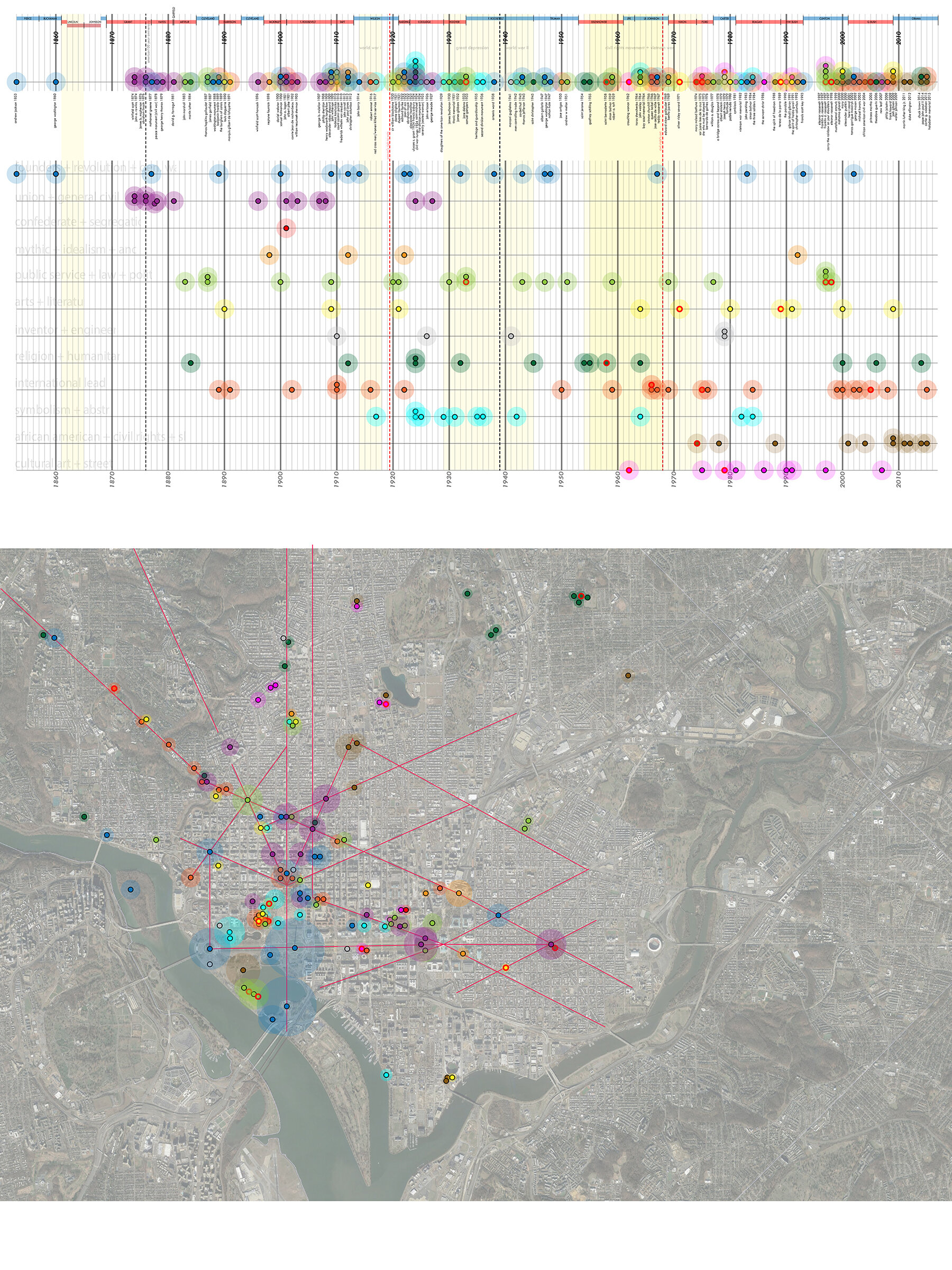

Where: Richmond VA & Washington DC

When: 2016-2020 [Ongoing]

This is an ongoing study, that has so far been completed in two phases: one study of the Richmond monument landscape as part of a 2016 Master’s thesis at the University of Maryland, and subsequently a 2018 study of the monuments in Washington, DC, resulting in the essay titled Statues in Social Context.

In this time of heightened American introspection, it is our collective responsibility to question the state and nature of our statuary. The persons in which we chose to memorialize in public monuments should be those who directly represent the ideals and virtues that society holds most dearly. The fluidity of the American societal ethos is one that evolves with time. A statue, on the other hand, remains a constant reminder of the collective morality and values of society the day it was erected. Through tumultuous generations of inequality it seems as though America has reached a new fulcrum of ideology which finally begins to value inclusion, empathy and morality over anything else.

Excerpt from 2016 Thesis (Richmond):

Confederate monuments are nodes along a major axial boulevard (Monument Avenue.) which bisects the core of the downtown and orients the entire flare of the city. The African American monuments pepper the interior streets of the historically black neighborhoods, or rest in rather meek nuances of the underutilized waterfront quasi-plazas. The Confederate monuments are also typically much taller, more concrete, and seemingly more eternally situated than their counterparts.

Introduction from 2018 Essay (Washington):

As if his command never ceased, the general mounts his horse with a certain vigor customarily not akin to a slab of granite. His twenty-two foot frame towers above the square which bears his name. Meanwhile, the historian is positioned as if he sauntered in on an afternoon jaunt, waiting for a passerby to strike up conversation. Seated on his bench of granite his modest figure rests in the park that bears his name.

Both remain eternally stoic in form, but their influence flourishes in the minds of the patrons who care to consciously visit. Objectively, the general is seen by thousands every hour. The historian is visited by a handful of visitors everyday in his shaded spot near the location where he once dwelled.

Each of these monuments commemorate men whose virtuous acts rank amongst the most profound and moral in American history. However, the gap in their statue’s influence on the collective unconscious is unmistakable. The flurry of commuters marching through McPherson Square glance up at Major General James B. McPherson and see an image of a true Union hero of the American Civil War. They see a white man on horseback poised in his wartime regalia. Even if their glance is not direct, this is the symbol of statuary that has been lodged into the subconscious aura which constitutes one’s idea of what a statue should “look like”. In Carter G. Woodson’s pocket park, the “father of african-american history” waits nearly alone for those who wish to come. The placement of his statue is immediately adjacent to the home he once occupied in Washington, DC; a notion that seems “correct” but also “convenient”.

Since 1876 (12 years after his death), Major General McPherson has projected an image of strength and heritage; an image that commands one of the largest public nodes of the nation’s capital. A cornerstone of Washington’s urban identity, he and other union generals organize the entire urban fabric of downtown. On the contrary, only during the Obama presidency, were statues of black men erected in Washington DC. Carter G. Woodson, received his commemorative monument in 2014 (65 years after his death) in a triangle in a historically black neighborhood.

Statues in Social Context - The Table Sessions [with Austin Raimond & Marques King]

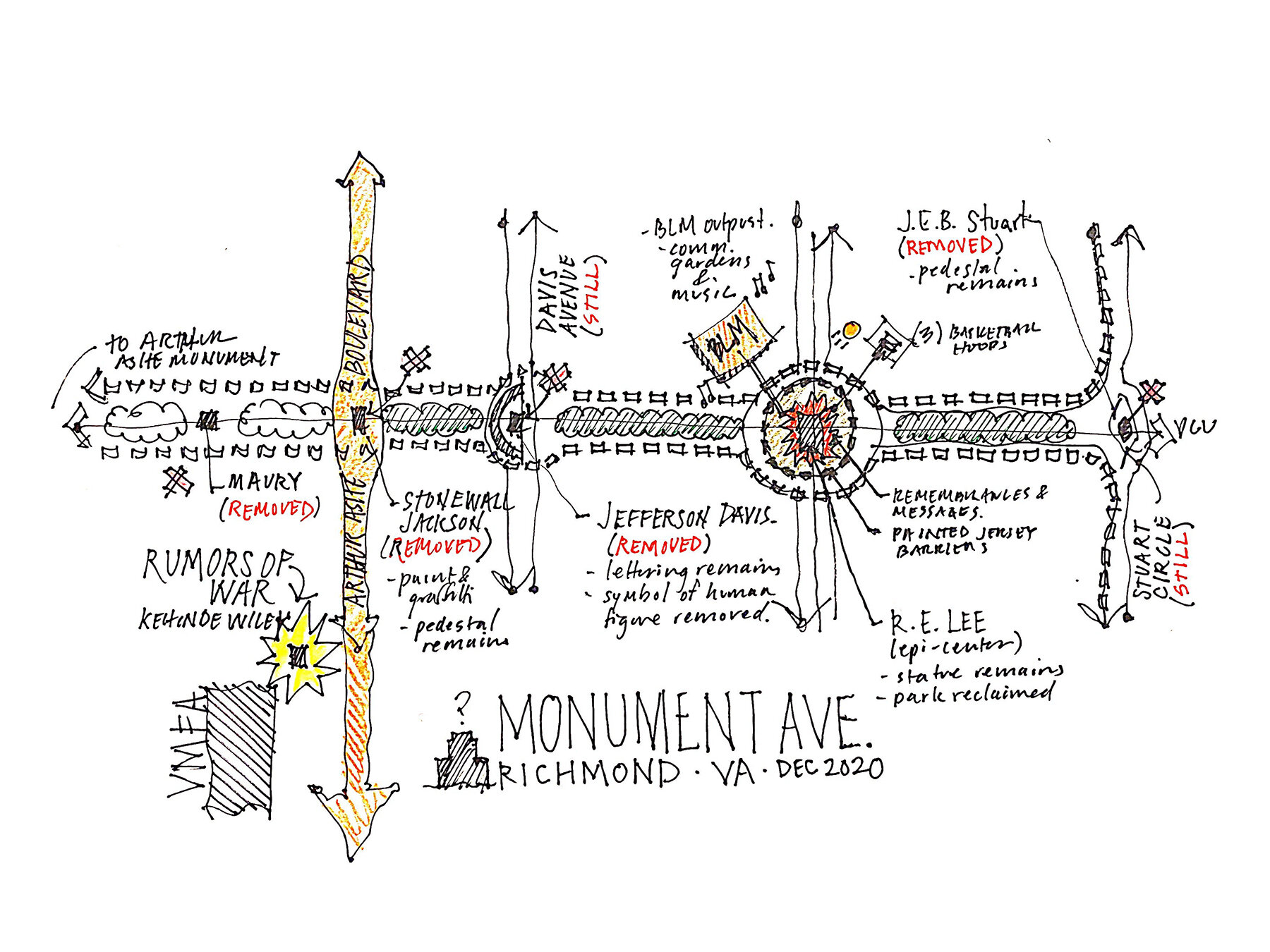

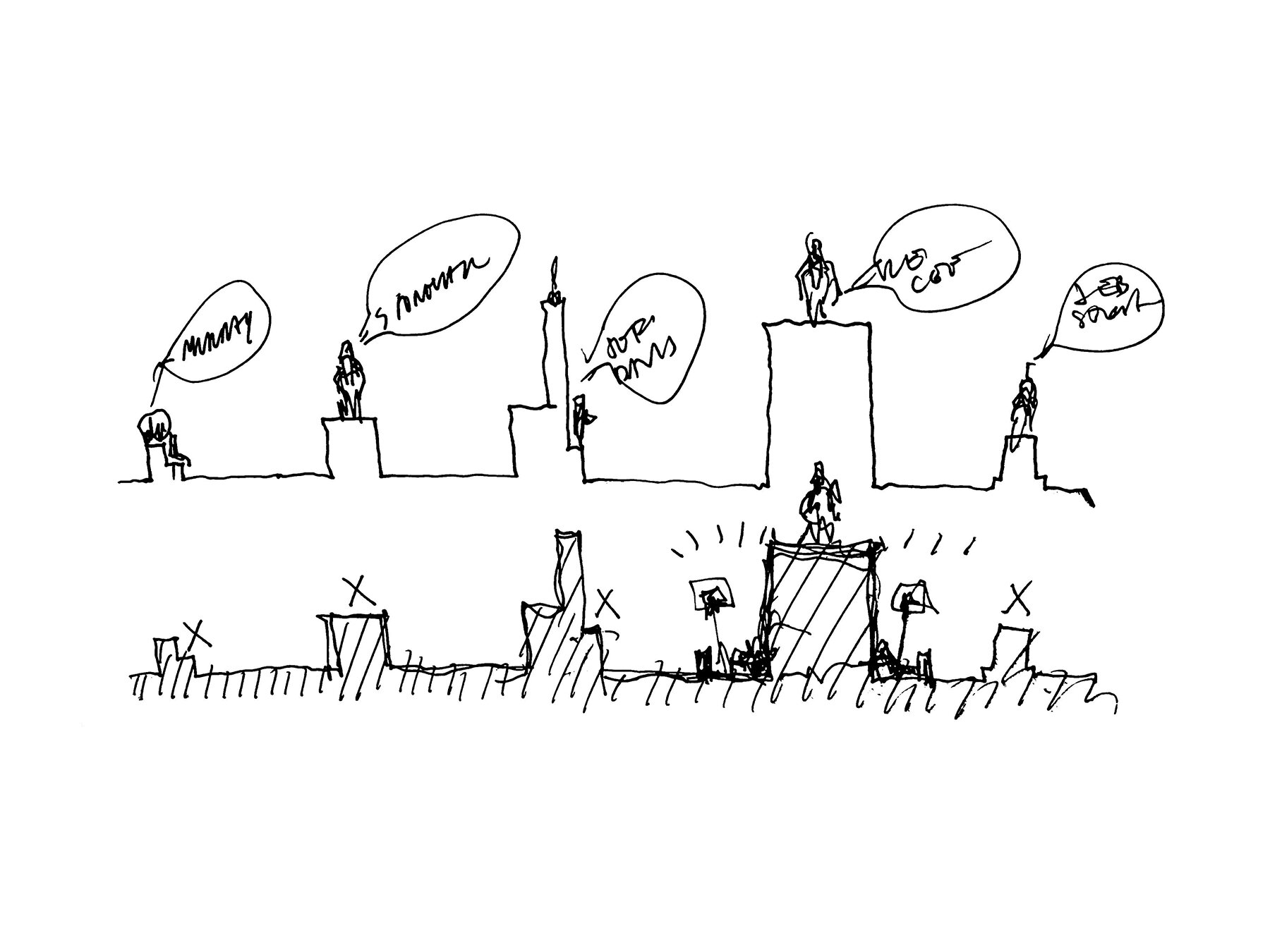

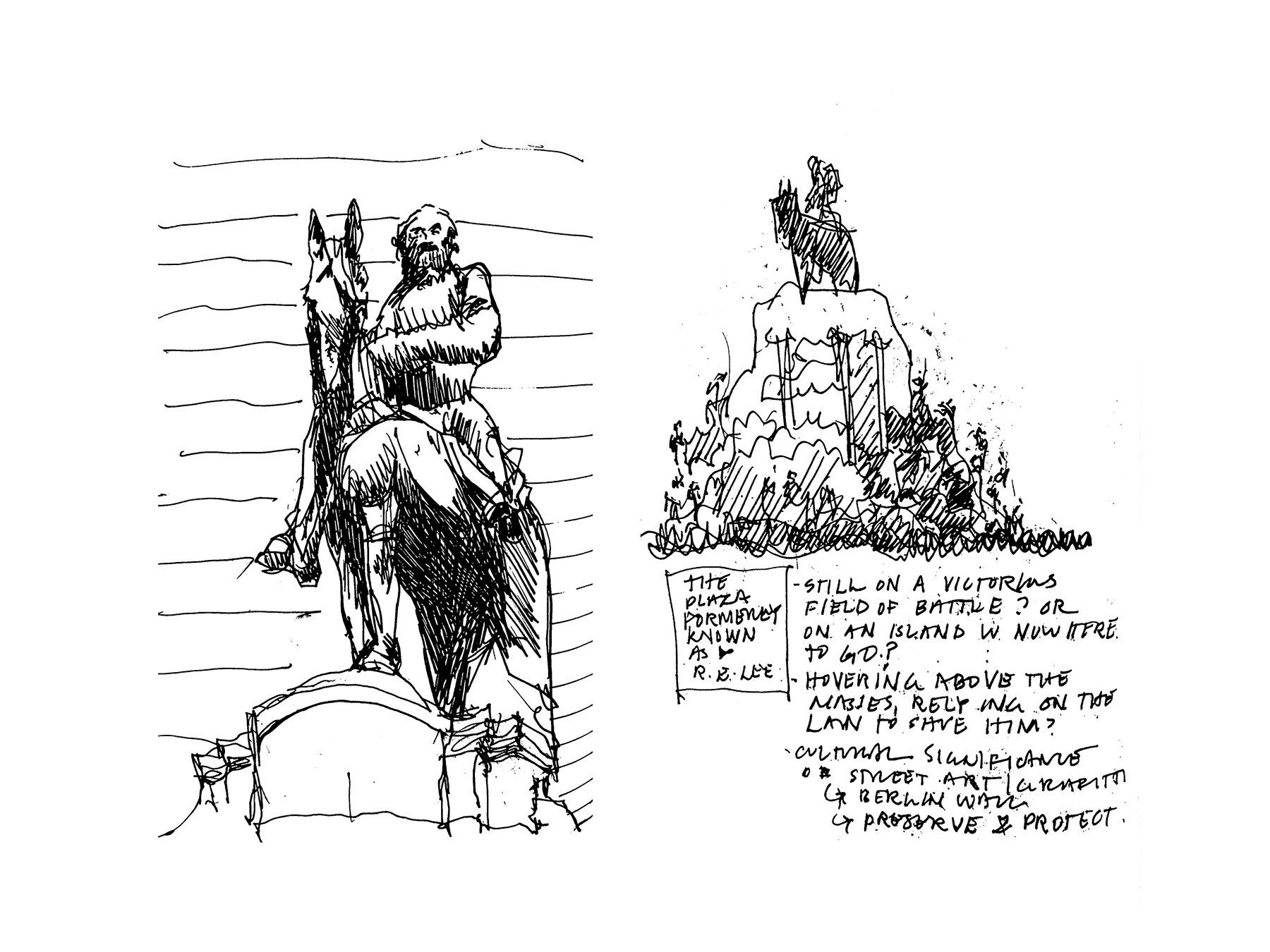

Observations from 2020 Site Visit (Richmond):

Most of the articles I’ve read about the removal of Confederate monuments in Richmond have included something akin to “I never thought I’d see this happen.” Which, given that the Robert E. Lee statue was erected 130 years ago, was the likely outcome. But, now that four of the five figures (with the last on the way) have been removed from their pedestals, it’s hard to imagine how it took this long. The Confederate statues in Richmond (and everywhere else) have always been prominent symbols of oppression, but the people who felt that oppression most deeply were not granted a loud enough voice for anything to change - until the dam broke in 2020 (a story we all know well).

We spent a few hours walking down Monument Ave last week, documenting, photographing, and reflecting on the in-between state of each of the monuments. Some are just blocks of stone with the human figures removed, with the faint outlines of this summer’s street art and graffiti. Others still have confederate symbology and remain anchors of streets named after people like Jefferson Davis. Impromptu basketball courts and community gardens have sprouted up at Robert E. Lee’s feet, with the street art of hundreds (if not thousands) and remembrances of those who have been lost. This is all to say that the conversation around these monuments has just begun, and the cultural significance of this new layer, the layer of expression that is still growing, is just as important as the monuments themselves.